Unless you live in the Southern Hemisphere, you’ve probably been enjoying the steady rise in outdoor temperatures. Gone are the 100(+) inches of snow in Boston, as well as the single-digit temperatures most of us dealt with in January. In its place is lovely spring-time weather, meaning you no longer have to grit your teeth in order to get out the door and train.

However, summer is around the corner, and with it … summer heat. It’s about to get hot. Very hot. And if it’s not hot, it will be humid, which still feels awful. (We’ll explain why in a second…) Just as running in sub-freezing temperatures takes a certain kind of toughness, running in the heat requires extra mental and physical stamina. It also requires a different approach to training and nutrition.

Generally speaking, there are two kinds of hot: dry hot, in which humidity levels are at or below 40 percent, and humid hot, which includes everything else. Depending on the moisture level in the air, your body will respond differently to the heat. You need to account for this change, especially if you have a summer race planned, so that you can create a nutrition and pacing plan to perform optimally.

Tweet this post! “It’s Hot: @SaltStick explains the difference between dry and humid heat: http://bit.ly/1Hx5EMM“

Dry Heat:

Because rainfall contributes to humidity levels, areas with very little rainfall (like St. George, Utah, which hosts the North American U.S. Pro 70.3 Championships) are prone to dry heat. While dry heat definitely feels hotter than dry cold, it doesn’t not feel nearly as hot as humid heat. This is because the body can efficiently cool itself with sweat, which evaporates quickly off the skin into the air.

Dry air is readily available to “accept” water, which means saliva and respiratory humidity, in addition to sweat, will evaporate quickly — especially if you are breathing hard. This results in the unpleasant “dry mouth.” Many endurance athletes report feeling far more thirsty in dry heat than in humid heat for this reason, even though the body tends to sweat more in humid heat at the same temperature. (Check out this forum, in which runners argue whether dry or humid heat has a greater dehydration effect, illustrating the deceptive effects of dry mouth.)

Humid Heat:

On the other hand, “humid heat” results from high levels of moisture in the air. Common to much of the Eastern half of the U.S., humidity makes the air feel significantly hotter. When the air is nearly saturated with moisture, sweat does not evaporate as quickly. This evaporation is a major method by which the body cools itself; thus, high humidity levels hinder the body’s ability to cool off. (Ironman Kona’s notoriety is partly due to the high levels of heat and humidity on the Big Island, where 86℉/30℃ can feel like 100℉/37.5℃ with 80% humidity levels.)

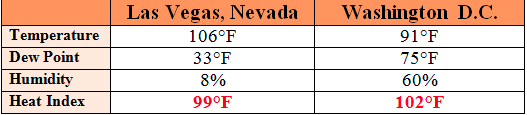

This increase in perceived temperature is partly the source of what’s known as the heat index, which is a formula meteorologists use to predict how hot the body actually feels, given a certain level of heat and humidity. This chart from Weather Works is a perfect example of how humidity can significantly increase perceived temperature. Note that while D.C. is 15 degrees cooler than Las Vegas, it feels three degrees hotter, due to the humidity.

Bored? You can actually calculate the heat index for fun: http://www.srh.noaa.gov/epz/?n=wxcalc_heatindex

While it may seem your body’s sweat rates are reduced in humid environments (because it just sits on your skin without evaporating), in fact, the opposite occurs. “In a hot, humid environment, in which ambient water vapor pressure is high, the body needs to increase the wetted skin area to achieve a cooling effect similar to that experienced in hot, dry conditions,” writes Jay Hoffman in Physiological Aspects of Sport Training and Performance.

In a 1991 heat acclimation study, researchers found sweat rates changed very little when athletes adapted to hot and dry conditions; however, in humid conditions, athletes’ sweat rates increased, especially in areas of the body with previously low sweat rates. Hoffman explains: “Greater sweat rates at body surface areas that already produce a large sweat concentration would have a minimal effect on whole-body cooling, because much of the increased sweat production would be wasted in dripping. In order to maximize efficiency of adaptation, the body selectively increases sweating in areas that previously had poor sweat rates.”

In other words, after acclimating to a hot, humid environment, you’ll sweat more, on average, than before.

Overheating:

In either case, overheating is a real and dangerous possibility. When it’s cold, it’s easy to attribute symptoms of overheating (sluggishness/difficulty maintaining pace) to fatigue. However, as Runner’s World points out, those same symptoms can mean more than just a lapse in mental toughness when it’s hot outside. Endurance athletes face a very fine line between pushing through the heat to improve fitness and pushing too hard.

This line can be blurred further when articles (like this one) detail how much pain professional athletes endure in hot races. For instance, retired professional triathlete Torbjørn Sindballe recalls: “My legs were starting to cave, my quads were gone and I began sliding into the place where I feel like I’m running on big stiff painful logs of heavy wood that are driven forward from my hip without any hint of technique whatsoever.”

“I picked it up and started to hurt myself like I have never hurt myself before,” writes professional triathlete Belinda Granger in the same article. “There was one stage with about 3K to go that I actually started to cry.”

We’re not criticizing these athletes for pushing themselves. There is a definite need to dig deep in races, but realize these athletes were under excellent supervision. Medical professionals are always at hot races, both at the finish line and throughout the course to make sure no one gets dangerously close to overheating. (Just ask the Chicago Marathon race organizers. In 2007, more than 300 people were picked up by ambulances along the course due to heat exhaustion.)

Our point is that a medically-supervised race environment is very different from running on your own, say through isolated trails. With that in mind, take note of these tips to keep yourself safe from the heat this summer:

- Phone a friend: If you’re planning on running for more than an hour in very hot conditions, make sure someone else knows where you’ll be, especially if you plan to run in an isolated area, such as a trail.

- Take it easy: Early in the summer, your body isn’t fully adapted to running in super hot conditions, which means you’ll have a higher-than-normal stress response to the heat. It takes about 14 days for heat-acclimation changes to occur physiologically.

- Pay attention to your body: This is probably the most important tip. There is a fine line between pushing yourself to greater fitness and pushing too hard. Feeling fatigued and hot are normal. Feeling dizzy, confused, nauseous, or cold (one of the most tell-tale signs of overheating) are not. Slow down until things return to normal.

We recommend light sweaters or smaller individuals consider 1 SaltStick Cap per hour. Heavy sweaters, larger individuals, or those in hotter conditions should consider 2-3 SaltStick Caps per hour. The best strategy for success is to practice your nutrition strategy during training so you can optimize for what works for you, and then execute that during racing. We provide a complete suggested usage guide here: Training with SaltStick Capsules.

If you know you’re overheated, the best thing to do is slow down. Drinking water and/or pouring some cool water over your head may help you recover quickly enough to continue with the workout. If not, it’s best to call it a day and find air-conditioning as soon as possible.

Overheating is not something you want to mess with. Dr. Peter Springer, medical director for emergency services for Volusia County, Fla. Springer told ESPN in a 2008 article, there are significant negative long-term effects of heat stroke. Says Dr. Springer: “About 15-20 percent of patients with heat stroke may die of the acute illness. While most will recover fully, some 10-15 percent will experience prolonged and/or permanent medical problems including neurological, cognitive and behavioral deficits from small strokes in the brain.” These “problems” can include sensitivity to light and sound, general fatigue, and trouble performing in hot or humid climates. Also, although a 1993 study found that long-term psychological damage from heat stroke is rare, the study’s authors cautioned that heat stroke victims should be monitored for several months after the incident to ensure full recovery.

Trust us. This last part we know from personal experience: It’s better to stop and accept the fitness gains you’ve made already than to push through and be sidelined for a week.